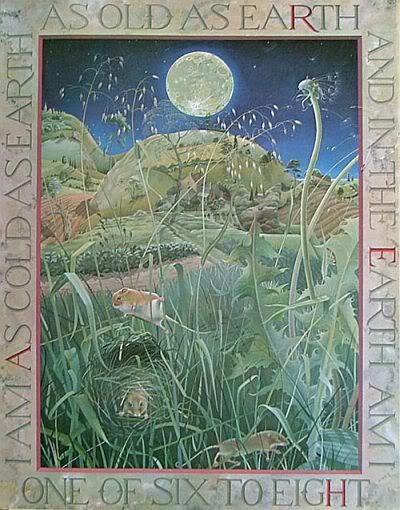

Kit Williams - One of Six To Eight (from Masquerade (1979))

When I started this 100days lark, I sat down at the kitchen table and made a list of artists. The first 70 or so were easy, names of Old Masters, great Modernists and more recent media friendly conceptualists and Turner Prize nominees sped from my pen. The last thirty required a bit more thought, retreating over my list searching for obvious omissions and names already written that would spark connections to other artists I’d missed. I had, for example written Max Ernst fairly early on in the list, but had forgotten his one-time paramour and fellow Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, similarly I’d listed Man Ray but somehow forgotten Lee Miller (and I can already hear Pete loudly berating me for this omission when he reads this on his return from work – Lee’s his one and only ‘Diva’) By this game of ‘artist association’ this list was soon full, now all that remained was the tricky bit of writing about them.

On Saturday morning though, as we were girding our loins and fortifying ourselves with caffeine and nicotine in advance of a quest into the great outdoors to hunt a Christmas Tree, we watched a BBC4 documentary – The Man Behind The Masquerade. Suddenly I realised that I’d managed to miss an artist off the list who meant so much to me, an artist who had probably influenced me more than any other.

There’s a snobbery about ‘illustrators’ as opposed to ‘artists’. While ‘artists’ make challenging works that question the world and its institutions, ‘illustrators’ merely make visual aids for storytelling. Yet it’s the work of illustrators like Shepard and Teniel, Sendak and Pienkowski who define our first encounters with images and whose work fires our childhood imaginations. These images teach us to look before we can read, without us even noticing, they change our worlds as much as any ‘Great Art’ can. To put them in a 'lesser' category because we experience them on pages in our own home rather than the walls of the hallowed spaces of the public gallery or the warehouses and lofts of Hoxton seems to me to completely underestimate the influence they have on our visual education.

Kit Williams’ Masquerade, published in 1979 told the story of Jack Hare, charged by the sun to deliver a lover’s gift of a fabulous jewel to the moon, somewhere along the journey the jewel is lost and the reader was invited to search the 15 paintings in the book for clues to its whereabouts, the artist having buried a non-fictional jewel somewhere in the UK.

Looking at the paintings again now, thirty years later, the art historian bits of my brain go into overdrive, noting that they seem to represent a kind of eccentrically English and pastoral Surrealism. The strange dreamlike collections of junk shop ephemera – seashells, puppets, cake stands and magnifying glasses – that appear in some of the paintings remind me of the works of Edward Wadsworth. The figures of pale boys, willowy girls and rosy cheeked, bulbous-nosed old men and their awkward poses seem descended from the figures in Stanley Spencer’s views of Biblical tales played out in the cobbled streets of Cookham. Going back further in time, I can’t help comparing the precise and detailed representations of flora and fauna to the flowers that dot every bit of spare space in Botticelli’s Primavera or to the nature studies of Albrecht Durer (his famous hare of course).

From technical point of view they’re brilliant paintings, sadly I’ve never seen any of Kit’s work face-to-face, but even in reproduction they glow with life and dazzle with detail, the translucent-skinned, contorted figures are forced, bursting by strange perspectives from the surface of the canvas, sometimes overlapped by and sometimes overlapping the trompe-l’oiel frames lettered with their cryptic riddles and hidden acrostics.

Yet on the BBC documentary, an art critic from the Times, cast doubt on whether or not Williams’s work could be considered 'Art'. She suggested that art should be new and different and that it should “reflect and talk about its time” and to her mind Williams work achieved neither. I’m always suspicious of those who say “Art should be this or that” as to me it seems to be imposing limits on something that by its nature should be a realm of infinite possibilities. But that prejudice aside, it seemed to me that she inhabits a completely different world to Williams. The private viewings and fashionable opening nights of Cork Street, Bankside and Shoreditch are a long way from the rural Gloucestershire circle of neighbours, collectors, admirers, and models (often the same people) to which Williams exiled himself 30 years ago, stung by the unwanted media attention that Masquerade attracted. But distance and difference do not make a world any less part of its time. Just because artwork speaks of and to a different world it does not follow that it does not speak at all.

Williams’s exile was used by the critic as further evidence of doubt as to the ‘Art’ status of his paintings. It was evidence, she suggested of a ‘lack of balls’, a failing that no true artists should have, as they dutifully hold up their works to scrutiny by critics such as herself. To me this seems again to be mistaking ‘my world’ for ‘the whole world’ and it seemed like a circular argument; ‘Art is only Art if I get the chance to judge it as Art’. A kind of self-justifying corruption of a Zen motto “If someone paints a painting in a forest and there’s no-one there to see it is it still a painting?”

Perhaps I’m being a little unfair to her, it is perhaps a critic's job to make such dogmatic pronouncements, it’s how they make names for themselves and has been since people have been writing about art, but still I was pleased when Turner Prize winner Keith Tyson, and the V&A curator Stephen Calloway (who has the greatest facial hair in the art world) spoke of the work, its craftsmanship and eccentricity with passion, and warmth. I expect the opinions of people who make art and who devote their lives to caring for it mean so much more to Kit than those who fill column inches attempting to define what it should be.

Of course none of the above mattered to the mind of the ten year old treasure hunter who dragged his father out on wet weekends to find the oak tree covered with dog roses on the Hogsback in Surrey where the golden hare was definitely hidden. (It wasn’t, my solution was wrong by about 60 miles*) but it started me looking at paintings in a different way, I stopped just ‘seeing’ them and started really ‘looking’ at them, decoding their secret messages searching for hidden meanings. The Masquerade paintings changed the way I thought about images and started my love affair with art in all its forms.

I may not have found the Golden Hare, but Masquerade gave me something far more valuable. Thanks Kit, I wouldn’t be who I am without your paintings.

(*If you want to know what the right solution was look here)

2 comments:

"Pie- Throwing"

If a person takes a pie into a theatre it is most unlikely that they are going to take it home with them regardless of the performance.

Rachel Campbell-Johnston (chief art critic of the Times) commented upon a body of work spanning thirty years without seeing a single painting and although she was invited to the exhibition, she never came...but she still threw her pie!

Hi,

Check out the trailer of my documentary titled "Artistas: the Maiden, Mother, and Crone," which features Leonora!

Sue May

Director/Producer

www.artistasmaidenmothercrone.com

www.mydogspotproductions.com

Post a Comment