(One from the archives – a bit of a cheat. Easy this blogging lark – give me a couple of weeks and I’ll be sticking up old shopping lists…

Back in 2008 a dear friend celebrated her 50th birthday and was looking for something new to challenge her. Knowing that she had an interest in things of a sci-fi nature, and that she’d never read any graphic novels I decided to chuck her in at the deep end and sent her the first volume of Grant Morisson’s ‘The Invisibles’. By way of an introduction to the books, and to the form of graphic novels generally I wrote the following.

Reading it back a year later it strikes me as a touch pompous, and it should be clear to the reader that I was still only just emerging into the sunlight after a few years spent locked in rooms with noting but academic books. Hopefully though, amidst all the references to Brecht, gratuitous uses of the word ‘text’ and the possibly slightly inaccurate details of this history of Graphic Novels, it still conveys something of my enthusiasm for The Invisibles. Enjoy.)

Wake Up!

I'm on a train to London and I'm yawning.

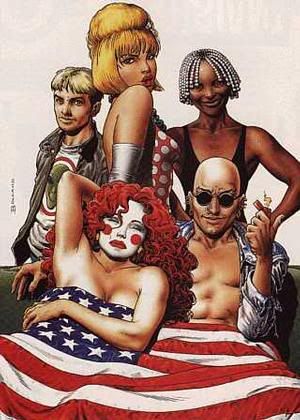

I’m yawning because of Grant Morrison. Last night I finished my fifth reading in as many years of The Invisibles, and I’ll admit that I thought I’d cracked it – I knew what BARBELiTH was, I knew who (or what) the Archons were and most importantly I’d finally managed to visualise the mental map of the conceptual universe that King Mob, Lord Fanny, Boy, Ragged Robin and Jack Frost inhabit. (It was two interlocking circles like a Venn Diagram with another circle enclosing them – imagine that in four dimensions and you’re close.) Such thoughts do not lend themsleves to a restful night's sleep.

But then came what King Mob might describe as the ontological shock – the moment of clarity, an instinctive feeling that you’ve made some sort of breakthrough, a breakthrough that becomes more and more preposterous as you struggle to frame it in the insufficient resources of language.

So far so metaphysical – I’m getting ahead of myself, but that’s what the Invisibles does, it gets into your mind like an itch. You can be sitting doing a crossword over a coffee and suddenly it dawns on you “Hang on a sec….that means that Tom O’Bedlam is really…”.

It’s a neat trick, don’t expect easy answers or plot resolutions with Grant Morrison – he has too much respect for his readers than to spoon-feed them, the majority of first time readers will often find themselves scratching their heads in confusion at the end of a chapter only to have a “road to Damascus” moment when you should be doing something else. If Grant Morrison is the Author/God of The Invisibles universe, his message to his creation is (to borrow from Robert Anton Wilson) “Think for yourself Schmuck”.

At the heart of The Invisibles, then, as with many comic books and graphic novels since the publication in 80’s of V for Vendetta, Watchmen and the success and increasing subversion of the medium by magazines such as 2000AD and Deadline, is the desire of the writers and artists to “activate” the reader, to change them from a passive receiver to an active participant in the narrative.

The eighties Graphic Novel Renaissance has been characterised principally in terms of writers such as Moore, Morrison, Pat Mills and Neil Gaiman deconstructing the mythic figure of the Superhero. Gone were the clean-cut defenders of Truth, Justice and the American way to be replaced with scarred, ambiguously moralled, sexually dysfunctional, tortured vigilantes. Consider Moore’s Killing Joke which culminates with the Joker and Batman sharing a joke and agreeing that all things considered the two had more in common than they’d like to admit, the hero and villain as two sides of the same scarred coin.

Certainly the ‘super-heroes’ in The Invisibles conform to this non-conformist redrawing of the ‘masked adventurer – a transvestite shaman, a fetish clad ruthless assassin, a psychic witch with a hidden past (or possibly future) and a ‘chosen one’ who just wants to indulge in booze, pills. a touch of anti-establishment arson and let Armageddon take care of itself. Unlike the ‘Golden Age’ DC and Marvel comic heroes it’s hard to imagine King Mob pausing mid adventure to advise kids to stay in school, to spike to teachers lounge coffee with peyote or to cover it in Situationist slogans possibly, but to stay in it, never.

This redrawing of the super-hero as a less-than-super human has been so successful that it has made its way into the mainstream, Batman Begins, X-Men and Spiderman mined this seam of damaged heroes to both critical and commercial acclaim.

It would be easy on first view to dismiss The Invisibles as another in the long line of “dark and gritty” comic books that now fill the bulging shelves of “Androids’ Dungeons” throughout the world, but there is more to it than that. The other aspect of the medium that has been explored in the post-Watchmen world is the subversion of narrative structure.

These days reading a graphic novel is not simply a matter of following a nice simple line of frames from left to right and down the page. These days frames dissolve, collapse and overlap. Often you find noticing symmetries, discontinuities and apparent non-sequiturs whose significances either may not be revealed for some chapters or, more abstractly, may act as what Berthold Brecht termed ‘distanciation’ – a pause or gap in the narrative to ‘shock the viewer into remembering that he is reading a text, for Brecht (as, it seems likely, for Morisson) such techniques were a political strategy, drawing his audiences attentions to similarities between what was going on on-stage and in the ‘real’ world. Gaiman and Moore use these devices extensively in their work, but it is Morrison whose work takes the structural warping of the graphic narrative further than anyone else.

In his earlier DC series Animal Man, Morrison broke new ground in comic booksby allowing is central character to slowly discover his own fictional status gradually coming to the realisation that the events in his life were guided by one GodAuthor for the entertainment of the GodReader, breaking the fourth wall, the hero turns shocked to the reader, looking out of the page in shock – “My God – it’s all for you!”

Of course direct address to the reader is nothing new – in Watchmen, Moore uses a number of devices to involve the reader – Rorschach’s journal, Hollis Mason’s autobiography and the interviews with Adrian Veidt, Sally Jupiter and Dan Drieberg that form the thematic epilogues of each chapter. Here, though, the address is to a fictional reader – one who inhabits the world of the alternate 1980’s New York.

Morisson’s reader however is not positioned as being of the Invisibles world, although frequently the characters seem aware that they are fictional in some reality or other, they also create new realities within their own, fictional, multidimensional worlds at whose borders the conflicts arise which raises the possibility that they may be creating our reality.

So, how does the reader approach The Invisibles? Simple answer…. “slowly”. Over years of lending Graphic Novels to friends, some of whom have been converted, some who haven’t, it’s occurred to me that there is an art to reading comic books. Pitched somewhere between literature and cinema, comic books require a different engagement to both. Frequently people make the mistake of paying scant attention to the pictures and charging through the words. This is natural of course, since it’s the way we’ve learnt to read since we discarded picture books in our childhood – we ‘read’ words but we ‘look at’ pictures.

Yet if we consider a frame of a comic strip as a accomplishing the same as a scene in a film or a paragraph in a book, moving along the plot through action or dialogue or action within the fictional world and providing a context within which these events take place, we can lose a great deal of the information that is necessary to understanding the narrative. The way we learn to read, focuses, naturally enough, on the words, pictures are somehow downgraded as we learn; our first books are nothing but pictures and as we graduate through the age-bands of children’s books, young adult books and finally adult fiction pictures disappear from our reading, bar perhaps a flashy illustration on the cover.

We are essentially trained to ignore the image in favour of the word, which to a 21st century Western eye holds the ultimate authority.

It is perhaps unsurprising then that the first encounter for the novice reader of graphic novels can often be an unsatisfying one – largely because he or she is putting all their energies into reading the dialogue, the thought bubbles, the sound effects and paying scant attention to the images. In the early days of comic strips this wasn’t a bad approach really – early cartoon illustrations do little beyond illustrate the dialogue which in turn makes sure that the reader doesn’t miss anything.

In the post-Watchmen world however, life isn’t so straightforward, these authors expect you to work, to examine the background of individual frames and indeed to look at the relationship of the frames to each other – often in Watchmen a similar arrangement of frames on the page is frequently used to draw parallels between the actions and motivations of different characters at different times.

The way that time unfolds in The Invisibles also throws narrative conventions on their heads. Again in the pre-Watchmen era following the sequence of events unfolding in a graphic narrative was a straightforward business – you were confident that whatever happened in the bottom right of a page happened after the events depicted in the top left. These days causality isn’t necessarily a matter of one event following another – flashbacks, flashforwards and, for want of a better term, flash-sideways’s are layered on top of each other and this is especially true of The Invisibles. We’re often introduced to characters out of order, events that seem to occur simultaneously at one point of reading are later revealed to be taking place hundreds of years in the past or future making keeping a diary of the events and adding in the dates later a quite helpful (albeit admittedly geeky) strategy for unravelling what’s going on - I must confess on my third reading I actually ended up with an XL spreadsheet in an attempt to map the timelines. Also worth bearing in mind is that fact that, since time travel becomes a central theme of the piece, events may happen in one order to one character, but in a completely different one for another (Keep a particular eye on Ragged Robin…)

So there we go – some rather garbled thoughts on how to read The Invisibles. The one fundamental rule is take your time – a rule of thumb that I try to use is to spend as much time on a frame as I would a piece of prose describing the events depicted. Keep an eye on signs, odd bits of graffiti, look carefully at characters in a frame outside the main action – most of the time they’re just window dressing but on occasions they may be playing their own part in what’s going on – although you might not realise until several editions later.

But above all enjoy it – The Invisibles will frustrate you, intrigue you and bamboozle. It’ll send you racing for Wikipedia to fill out gaps in your knowledge; it’ll make you laugh, cry and gasp. Most of all, it’ll make you think.

Welcome to The Invisible Kingdom – all that’s left to decide is “Which Side Are You On?”

No comments:

Post a Comment